From: bostonglobe.com

In the late 1980s, Jon Hirschtick was part of one of those fresh-from-the-lab MIT start-ups in Kendall Square. He and his co-founders were in their 20s, and they understood more than most people about how computers were about to upend the way products were designed and manufactured — a field called CAD, for computer-aided design.

They made a big bet that engineers were ready to use PCs and a relatively-new operating system called Windows as part of their job. (Microsoft founder Bill Gates stopped by the office one evening to get a demo of their software.) And they felt lucky to have raised $1.5 million for the venture, as Boston investors “presumed you needed to be old to be successful,” Hirschtick says.

So much has changed in 27 years.

Kendall is now too pricey for startups, so Hirschtick’s new company, Onshape, is headquartered in a tucked-away Alewife office park. There is no foosball or ping-pong table in evidence, no scooters leaning against desks. The average age of the founding team is over 50 — one founder, Tommy Li, came out of retirement. And this time, the crew has a notable track record, so they barely broke a sweat raising $64 million from investors.

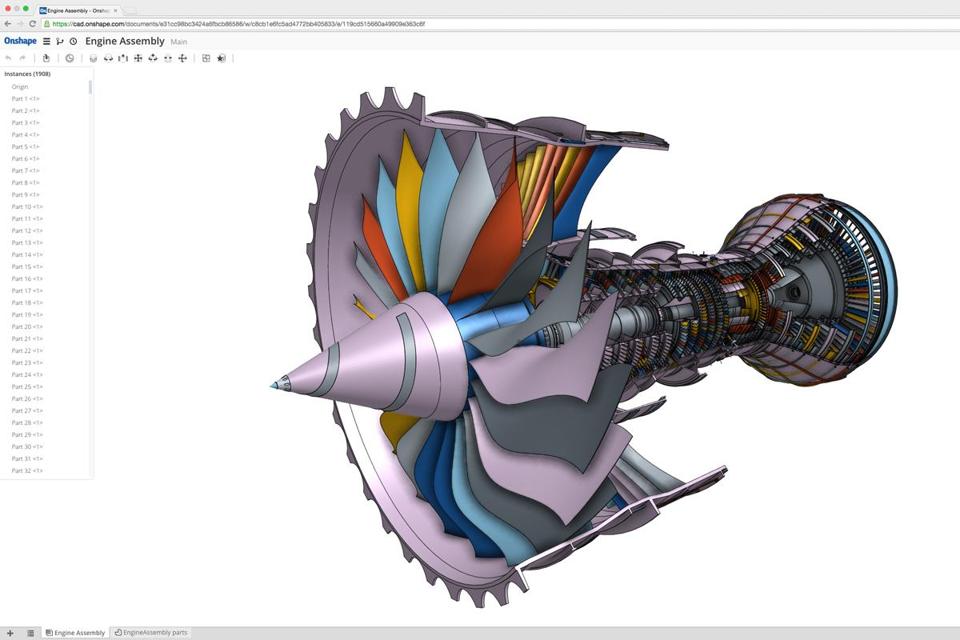

But they still talk like 20-something disruptors. Onshape’s founders contend the world of CAD software, long dominated by big players like PTC of Needham, California-based Autodesk, and Dassault Systemes, the French software maker with a major campus in Waltham, has grown stagnant. What a new generation of designers and engineers desire, they say, is powerful software that doesn’t have to be installed on your own machine — think Google Docs — and can be accessed with any device, even a smartphone.

CAD software is used to create just about every mass-produced item you encounter in the world, from a jet engine to a surgical instrument to a soda can. And, Hirschtick points out, as more hobbyists and amateur “makers” purchase 3-D printers, they, too, must learn CAD software to crank out custom toys, napkin rings, or phone cases in their basements.

The CAD market was still young when Hirschtick started his first company, Premise Corp., in 1987. Premise made a $1,900 software package that tied equations and spreadsheet formulas to mechanical drawings so, for instance, a connection between two parts was thick enough to handle stress. Prospective customers praised the software and said they would place orders — but not enough did.

“Everyone liked it,” Hirschtick says. “Liking is great, but buying is better.”

Premise was acquired by a larger company, Bedford-based Computervision, in 1991, but the deal wasn’t a blockbuster.

If Premise was a Honda Accord, then Hirschtick’s next startup, in 1993, was a Ferrari. He used money he made playing on the MIT Blackjack Team to rent office space and bankroll the development of new software.

Most engineers were still using expensive workstations made by Sun Microsystems and IBM to run CAD software. Hirschtick’s second company, SolidWorks, again bet on Windows — but this time there was a new generation of PCs with more powerful Intel chips.

SolidWorks users could simply click and drag elements of a widget to move them around. When the software debuted in 1995, a trade publication called it “possibly the best ever” first release of a CAD product. Two years later, SolidWorks was bought by Dassault Systemes for $316 million. Today, SolidWorks is used by about 62 percent of engineering professionals, according to a 2013 survey by the site CNC Cookbook.

Hirschtick was still working at Dassault when he had a revelation. Late in 2010, Google released a project called Google Body — a way to explore and manipulate a three-dimensional anatomic model using a web browser. “I just jumped up from my desk,” he says. To Hirschtick, it was a flashing neon sign that web technology was sophisticated enough to build CAD software that existed entirely in the cloud.

Hirschtick resigned from Dassault, and, in November 2012, began putting the band back together. He hired people he worked with at Computervision and SolidWorks, like John McEleney, now chief executive of Onshape. They hired people McEleney worked with at his prior start-up, CloudSwitch. And they attracted a big gun as their chief financial officer: former Harvard University CFO Dan Shore.

The mission was to build a CAD system that wouldn’t entail installing software — and one that could basically sell itself, with a free trial for casual users and a $100-per-month model for those who want to use it regularly. They’ll unveil it Monday.

The demo is impressive. As a user, you can watch live as someone on your team makes changes to a fan blade — even if she does it on a phone or laptop a continent away. Onshape keeps track of who changes what; it can allow several different versions of the fan blade to be designed in parallel.

The questions facing Onshape are the same confronting many startups. Established firms are making noise about shifting their product offerings to the cloud. Engineers are already comfortable with existing CAD software. Can Onshape carve out a place for itself?

Hirschtick acknowledges that expectations are different when you’re no longer a bushy-tailed 20-something. “Not to be immodest,” he says, “but this time around, we’re more like the guys who won the Super Bowl last time — people have unbelievably high expectations that this will be another SolidWorks.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.