The West can lead again if America recovers its self-confidence, argues John Micklethwait

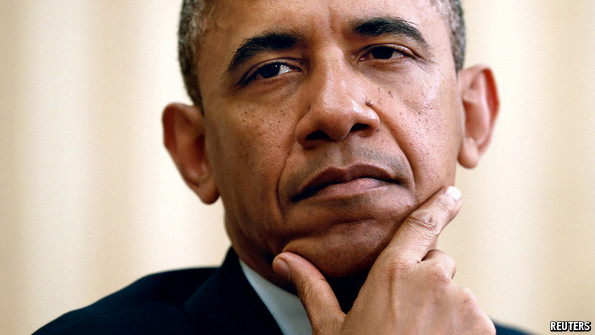

For most of the past decade the world has got used to the idea of influence moving slowly from America to China. The “Washington consensus” of democracy and free markets has given way to the Beijing consensus of authoritarian modernisation. America’s self-confidence has been battered first by George Bush’s clumsy war on terror, which gave democracy a bad name, then by the credit crunch, which did the same for Western finance, and finally by the dysfunctionality of Congress, which shut down the American government in 2013. China has become bolder about asserting its rights in Asia, while Barack Obama has seemed a defensive president, retreating from Iraq and Afghanistan, unwilling to guide the Arab awakening and keen to “outsource” responsibility in other regions to local powers.

In 2014 the balance will shift back: America will look stronger and China will look less alluring. The question is whether the cautious Mr Obama will use this to leave a mark on the world.

The changes begin with the economy. China will still grow faster in 2014, but America, having cleaned up its banks and repowered its factories with shale gas, is closing the gap. Indeed, measured at market exchange rates, America’s contribution to global growth is likely to be bigger than China’s—for only the second time in eight years. It will be decades before China’s income per head (only $11,000 in 2014, even when adjusted upwards for purchasing-power parity) matches America’s ($55,000).

Meanwhile, on the corporate level, American management is recovering its mojo. Back in 2009 China’s state capitalism seemed an attractive alternative: four of the world’s ten biggest firms came from China, compared with just three from America. Since then investors have learnt that “state directed” can really mean “interfered with”. By 2013 nine of the top ten were American, with PetroChina the only exception. A banking crisis of some sort is even possible in China in 2014: too many loans have been made to different branches of the bureaucracy and the crony companies that live off it.

That points to the other area where things will even up in 2014: government. There is little prospect of Washington looking much healthier, though Republicans in Congress may become a bit less mindless in the run-up to the mid-term elections in November. But the idea that China is run by a meritocratic elite of shrewd long-term planners may come more into question—especially at the local level. Ever more stroppy middle-class parents are taking to the internet to complain about poor schools and lousy health care. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has started a campaign to improve local services and stamp out corruption.

But the graft is not only at the bottom. The show trial of Mr Xi’s erstwhile rival, Bo Xilai, opened many Chinese eyes to the opulence of the country’s princelings. Americans may moan about money politics, but the wealth of the richest 50 members of Congress is $1.6 billion, compared with $95 billion for the richest 50 members of China’s People’s Congress. More such revelations will surely come.

None of this means that China is going to stop growing. To some extent all that is happening is a reminder of America’s deeper strengths, many of which never went away. Both Mr Bo and Mr Xi sent their children to Ivy League universities. But perceptions matter. And, as America re-emerges, the Beijing consensus may look less enchanting to citizens of the emerging world.

That leaves Mr Xi and Mr Obama with rather different challenges. For Mr Xi the focus will be ever more domestic: he needs to clean up China’s government and build a welfare state for its demanding people, albeit one that borrows more from lean Singapore than from flabby Washington, let alone clinically obese Europe. Foreign policy is a distraction.

A world of opportunity

Mr Obama, no doubt, would also like to clean up American government. There is a big deal to be done to right America’s finances. But Mr Obama has shown little appetite for reform, and the Republicans don’t trust him. Like many second-term presidents, he will increasingly focus on matters abroad. Now that America looks a little stronger, might he become a little bolder?

One reason to hope he might is that “the Bush excuse” must surely now have expired: it is not enough for Mr Obama to claim that he is less awful than his predecessor. Meanwhile, the cost of inaction is mounting. If Mr Obama had helped impose a no-fly zone in Syria in 2012, then Bashar Assad would probably have been toppled and thousands of lives saved (and Vladimir Putin would not have come to be seen as a peacemaker). Wherever America has stepped back—Latin America, eastern Europe, Africa, the Middle East—it has created an unhealthy vacuum.

Look around the world and there are a surprising number of opportunities for a slightly more ambitious president. Some are in the “last chance” category, including those two familiar bugbears in the Middle East: Iran, which is ever closer to gaining a nuclear bomb (seearticle), and Israel-Palestine, where the chance of a two-state solution is ebbing away. Free trade, across the Pacific and the Atlantic, offers a big prize both economically and strategically, if it gets a determined push from the top in 2014. In Latin America the disappearance of Hugo Chávez gives Mr Obama a chance to unite the continent. Africa has yet to hear much from America’s first black president. India, frightened by China, might listen to America more now that Anglo-Saxon capitalism looks a little healthier. And so the list goes on.

None of these things requires the only superpower to take on the imperial arrogance that so disfigured the Bush presidency. Nobody wants invasions or democratisation by force. But in 2014 the world will crave leadership. Mr Obama should deliver it.

John Micklethwait: editor-in-chief, The Economist

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.